This post is an excerpt from a book by my husband titled The Twilight of Bohemia: Westbeth and The Last Artists in New York. It is about the changing status of art and artists in New York City between the 1970s and today; it is focused on a government funded housing project in Manhattan, an anomalous experiment called Westbeth.

Westbeth was created for artists without judgment on the quality of their work, the criterion being more about dedication and demonstrated ability to publish/show work. Peter’s book is primarily about the people who live(d) in the building; some of them became extremely successful and even famous (photographers Bob Gruen and Diane Arbus lived there) but most did not even become known, at least not to the wider public. (Indeed the most unifying presence in the book is a brilliant anonymous painter and lost soul named Gay Milius whose life and death personified the mercurial spirit of his time as well as the changing nature of Manhattan’s art culture.) Regardless, in this environment all had the chance to flourish, not only because of the much reduced rent but because the exchange of ideas inherent in such close proximity to one another. Creative nurture was made possible; eccentricity also flourished and sometimes they were the same thing.

I originally posted this excerpt nearly two years ago but I took it down when the publisher had a cow about the timing; it’s fine to do it now as the book is just out. But now…is very different. In March 2023 it seemed possible for the present to dialogue with the past, or to at least feel on a continuum with the past. Now any continuum feels twisted unrecognizably by 1) the technological and epistemological rupture of AI, which seems to turn art-making into a job done better by machines and 2) by a government that views art as something to be ideologically attacked, defunded and tased into submission. In such a context The Twilight of Bohemia is truly poignant, a glimpse of a vanishing world.

In the book, this world is illustrated by stories told through dozens of people who live(d) in Westbeth, so it was hard to choose one person to focus on for this excerpt. Peter picked Christina Maile because he loves her work, but also because she’s lived in Westbeth from it’s beginning, and particularly embodies its ethos. She has been a continuously working artist her entire adult life, moving seamlessly from one art form to another without special training, and who has integrated that work with the dense loam of family, day jobs and community. I hope you enjoy reading about her and seeing a few of her fantastic pieces.

From The Twilight of Bohemia:

Westbeth is a vast building—actually a complex of buildings—that occupies the square block between Bethune and Bank Street and Washington and West Streets in New York’s far-West Village, a neighborhood more fashionably known as the Meatpacking District. It contains 383 apartments that range in size from studios negligently sandwiched between stairwells and elevator shafts to spacious triplexes reserved for families with two or more children. Thanks to a system of subsidies supported by the J. M. Kaplan Fund and various entities of the federal and city governments, all apartments rent for a fraction of the going rate in the surrounding neighborhood. The tenants are artists, mostly older artists, many of whom have lived there for fifty years, kept in place by the low rents inside and the unforgiving housing market elsewhere in the city. I sometimes picture them as astronauts on a spacecraft that has come to ground on an alien planet, or maybe, as in the Planet of the Apes movies, this one thousands of years in the future. Inside there is warmth and breathable air and the company of creatures like themselves. Outside the atmosphere is poisonous and the sun is weak, and the inhabitants are so demonically robust that it’s hard to believe that their ancestors were human beings.

Westbeth has been home to painters, sculptors, dancers, playwrights, composers, photographers, poets, novelists, and at this writing one puppeteer. Some of these people achieved fame and maybe even greatness—Diane Arbus, Hans Haacke, Muriel Rukeyser, Lorraine O’Grady, the pioneering video artist Nam June Paik, the cheerfully perverse multimedia jester Barton Lidice Benes, whose materials included millions of dollars in shredded currency and his own HIV-positive blood. (Authorities in Sweden once threatened to impound the items in one of his shows unless they were heated for two hours in a 160-degree hospital oven.) Many more remained obscure—some maybe deservedly obscure, though anyone who thinks that success in the art world is indicative of merit is either dishonest or a boob. To me, much of Westbeth’s interest and moral grandeur arises from the juxtaposition of genius and mediocrity and even the kind of outlandish artistic ugliness that made one tenant (in speaking of another) clutch her head in disbelief. “How could this be the focus of someone’s entire life!?” Anyone familiar with the ecosystem of artists’ subsidies, the pitiable scarcity of funds, the remorseless, termite-like competition for them, would probably agree. But not being an arts administrator, I wonder why weird art shouldn’t be the focus of someone’s entire life. People have devoted their lives to worse, often on the government dime.

Christina Maile learned about Westbeth in 1970 when she moved to New York with her first husband and was urged to apply by a college friend who was working for the architect Richard Meier. Meier was at the beginning of his career and had had only one commission, a house he’d built for his mother, but he’d been hired to gut the interior of a massive complex of buildings in the far-West Village that had been the laboratories and offices of the Bell Telephone Company and repurpose the space as subsidized housing for artists. ‘Repurpose’ was a new word, and one with radical connotations at a time when nothing was ever reused, only junked and replaced by something new. No project like it had ever been undertaken in the U. S., not in terms of size (the footprint was three quarters of a million square feet), or funding source (a partnership between the nonprofit J. M. Kaplan Fund and the fledgling National Endowment for the Arts), or beneficiaries. Who cared about artists back then except maybe the Guggenheim Foundation? Even Diane Arbus, who would become one of Westbeth’s early tenants and among the first of its many suicides, was getting less than $100 an image; the Smithsonian paid her only $25.

A further anomaly was that the primary criterion by which applicants were admitted wasn’t the quality of their work. Joan Davidson, the president of the Kaplan Fund, remembered asking the original admissions panel how one would define quality. "Who’s going to decide? So should we have juries? No. Should we have site visits? No. These were big discussions, but in the end, I think we mostly agreed, 'No, we’re not arrogating to ourselves. You know, we’re not an arts institution. We’re housing!'” Instead, Westbeth looked for applicants who demonstrated commitment to their art form, as measured by the frequency and currency with which they showed or published or had work performed. (Perhaps no tenant in Westbeth’s fifty-year history has been more committed than the painter and illustrator Karen Santry, who after her basement studio was flooded during Superstorm Sandy in 2012, purchased a wet suit and flippers and dove down into the toxic stew of water, oil, and solvents to salvage some of her work. At the time she was in her sixties.)

Christina Maile was a playwright who'd already had work staged. Her mother was Trinidadian, her father an indigenous Dayak from the island of Borneo. They met in New York and raised Christina and her sister in Bedford- Stuyvesant. The family was poor. She must be in her seventies now, but she's still youthful-looking, with thick, black hair framing soft, rounded features. She often seems wryly amused by her recollections, even those that involve quarrels, embarrassments, and disappointments. "I'm not sure how, what the criteria were, and how they looked at the admissions, but it was an area of the West Village that nobody wanted to be in. We walked up and down Hudson Street when it was really quiet—you can't believe how non- populated it was—and we said, If we get in, we get in; we don't get in, we don't get in, because we couldn't—" briefly she becomes shamefaced—"find the place. We were a little leery because it was the meat market then. There was a lot of, you know, just blood and bowels and cow parts. And there was the Men's House of Detention down the block, so it looked like a kind of suspect area. But we decided that it was great. And a couple of months later, they told us we had been accepted, and we moved in."

The neighborhood had the arctic loneliness of wind-scoured streets and meat-packing plants whose doors clanged down at three in the afternoon, of block after block without a restaurant or laundromat or bodega. In places it was dangerous. People didn't venture beneath the West Side Highway overpass unless they were parking the car or wanted to get their cock sucked or suck somebody else’s.

There was also crime inside the building. "We had maintenance men who stole from the apartments," she recalls. "So that was kind of scary, because you didn't know which maintenance man was doing the stealing. And then there was a whole series of muggings a couple of years later. That's why we had the tenant patrol.”

Few of us see the events of our lives in terms of a larger history; really, most of us live as if there were no history or as if the thing they call history had nothing to do with us. In the same way, most Westbeth residents relegate the community's history to the background of their stories. Maile, however, presents that history directly, as if she were appointed for that purpose. She became part of the Westbeth Playwrights Collective, which later evolved into the Westbeth Feminist Playwrights Collective because, she says, "the men just wanted to write their own plays whereas the women wanted to write about feminist issues. At that time women's lib was a really hot topic. We had two goals in mind: one was to present plays that were sharp and quick and satirical but also loaded with elements of rebellion and meaning; and the second goal was to provide job opportunities for women backstage in those trades that men usually occupied." The set designer, set builder, lighting technician, and sound engineer were all women. The Collective's first evening of short plays was called "Rape-In." The jaunty title (see Be-In, Sit-In, Love- In) was a provocation. It opened on a Wednesday night at ten P.M., and in spite of the inauspicious hour the theater was packed.

As a couple with one child, Maile and her husband got a simplex, a two- bedroom laid out on one floor. The ceilings were high, the construction was solid. “You could do anything you wanted in your apartment. You could build a loft bed, you could take down a wall, you could move the refrigerator, you could add a second bathroom, you could modify the stairs, you could do anything. You didn’t have to ask management.” A further benefit of their new home was that "people. . . didn't look at you weirdly because you said you were a musician or a painter. I mean, there were people that understood the need for however you behaved in public." For all this, she remembers paying somewhere between one hundred and sixty-one and two hundred dollars a month. "It was a little high for us at the time," she says, deadpan.

"A day to day thing with me, because I had kids, was my husband went to work, and then I would go down to the play co-op in the basement because the mothers put together a co-op so we wouldn’t have to watch our kids all the time. They would be there for a couple hours. And then I would try to write in that time, and then afterwards my older kid would come home from school, and there would be a lot of kids coming in and out getting snacks. And then at night, we'd go over to our next-door neighbor. Someone in the building was selling grass. So every night we would have these long, intense conversations about art. The next-door neighbors were a painter and an actress. So we talked about theater and then we’d keep getting stoned and then the kids would come in and we’d pretend we were not stoned, and we’d give them cookies and make them go back to bed.

"Everybody was young. So there wasn't that thing that happens as you find your world narrowing. Everything was still open for success, for acclaim, for children growing up happy. There was synergy: everybody understood each other when we talked about things. It was never, I don't understand how you can paint all day. No one would even think that. But at the same time, there were also eccentric people who didn't like anyone. They never joined in. It’s not that they were terrible, It's just that everyone understood that they didn't want to be bothered. Sometimes you’d see them carrying paintings inside the elevator, or in summer they would be dressed in really heavy wool clothing because that's what they wore all the time."

Over the next twenty years, Maile left the theater, supported herself as a carpenter, and then enrolled in the landscape architecture program at City College: “You’ll see how shallow I am,” she warned me. Designing stage sets for the collective had gotten her interested in volume and space, which in turn got her interested in architecture. But City College’s school of architecture had a long list of requirements, including calculus. The architecture building also housed what the college called the urban landscape program: it had no math requirement. (Maile’s entire career was influenced by her distaste for higher mathematics.) On graduating, she went to work for New York City’s Parks Department. “I love the Parks Department because it has a real impact on people's lives. I mean, the Parks Department, interestingly, enough, doesn't only do the playgrounds and parks, they also are in charge of all of the historic landmarks, like the Diamond House, for example, or the Jumel Mansion, or Washington Square. They're in charge of restoring and maintaining historic landmarks. And they're also in charge of all the recreational stuff. They're the pools and the pool buildings. I mean, they have such an impact on the cities. And when I was there, it was one of the smallest departments. And yet it had really a lot of influence on how people live in the city My work was mostly in Manhattan. But once I had to do some restoration in an area in Prospect Park, and Prospect Park is really beautiful. I like it actually better than Central Park because Prospect Park is a much more sinuous, organic kind of shape. There are little paths that people have forgotten, and so the area that I was assigned to renovate was like a room in a big house that everyone has forgotten.”

Once she was called on to clear the roof of a derelict concession stand of a gigantic turtle that had probably been a discarded child’s pet but now was too big and heavy and sullen to be easily removed. Thrashing and snapping, the turtle was packed into a rubble-bag and lowered from the roof by pulley, then loaded into her car. Maile and an assistant took it to a wildlife sanctuary in New Jersey. There they prodded the turtle out of its bag and watched it trundle into the brush. Maybe it’s still alive there. Somewhere during this time, she began painting and making prints, using a vacant studio in Westbeth’s basement. As a landscape architect, her job was to make nature compatible with the needs of the humans who passed through it. To make nature enjoyable. The art she was beginning to make represented nature in a different way. She wanted to show “nature when man's hand is not on it. I thought that would be really a nice thing for people to have instead of everything being so designed and cosmetic and not threatening. Because nature should be threatening and surprising and unexpected.”

Perhaps this sentiment is what she tried to express in “The Red Bear’s Dream,” a polyester plate lithograph dominated by the figure of a gigantic bear with fur the color of a dying coal standing on the edge of a lake in the middle of a dense forest. The trees that crowd overhead cast trembling reflections in the water. Both the trees and their reflection are entirely black and white. Apart from the bear, the only spot of color is a small—really a tiny—woman in an orange jumper who confronts the bear from atop a rock or hummock at the lake’s edge. Bears’ faces are notoriously inexpressive; it’s part of what makes them dangerous. You can’t necessarily tell when one is about to break your neck with a swipe of a paw. But this bear looks perturbed. Maybe it’s thrown by the sight of another point of color in a newsprint wilderness.

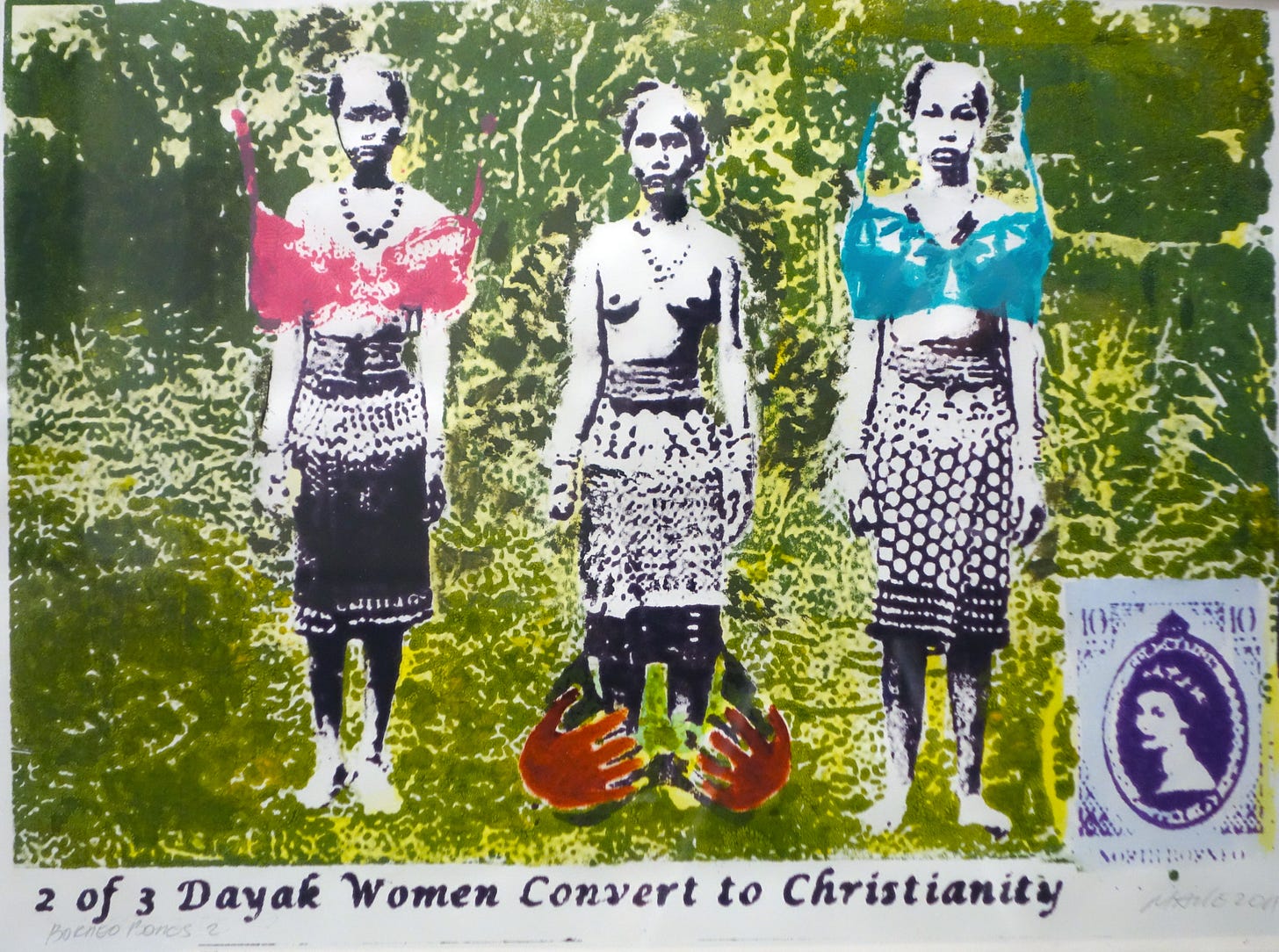

Maile often represents nature as a monochrome backdrop for brilliantly colored human and animal figures, as well as for hybrid ones: women with the heads of birds (“Birds have seen everything! They’ve flown over oceans, they’ve dived into valleys”); mothers and children you might see in any park in New York if not for the Baluba masks that cover their faces; a tree that grows from the hips and legs of a naked woman, surveyed by a row of saints that might have been copied from the dome of St. Mark’s. The artist likes multiples of things: gemlike dead hummingbirds that recall the ones John James Audubon killed by the hundreds and then reanimated in his paintings; Dayak children posing for a photograph beside a terrifyingly robust white priest, the children anonymized by the yellow skulls painted over their faces; soldiers and toy soldiers; bombs sailing down a waterfall to be collected by faceless men in white hazmat suits. The duplicates might be inspired by the Xeroxed band posters that conquered New York’s streets in the seventies and eighties. You couldn’t walk down Bowery without seeing the Dead Boys, Mars, and the Contortions layered on every wall and lamppost, each image multiplied hundreds of times. Duplication occurs in nature, but I think of it mostly as an industrial process, executed with molds and stamping machines and, more lately, 3D printers. In Maile’s work duplication signals man’s hand on nature, leaving its greasy fingerprints on it: if you didn’t know better, you might think nature was man-made.

She says, “I think a lot of my work is basically storytelling. I've been deeply influenced by my father’s stories about growing up in Sabah and my mother's and grandmother's stories about their life in Trinidad. My mother and grandmother lived both in a supernatural world and then the natural world. Part of it, I think, was that they had not fully assimilated being in the U.S. So some of their stories were really kind of training for how you deal if you happen to meet a ghost on a lonely road. Or, in my father's case, if you happen to meet a giant boa constrictor, don't mistake it for a log.

I asked her about a piece in which period photos of three Dayak women are placed against a tinted backdrop of tropical brush. Two women have brassieres painted over their breasts; the third is bare-breasted, but if you look down you see that a pair of cupped hands is lying at her feet. Maybe they’re about to climb up to her chest like predatory crabs. Maybe they already tried that and she threw them off. The work is titled “One in Three Dayak Women Convert to Christianity.” Maile told me, “I did go to Catholic school for twelve years, so I was really invested with a lot of religious imagery and symbolism. I understood why the missionaries felt a need to convert ‘the natives,’ quote, unquote, because of this belief that they were imparting the truth about how to live your life and the truth about that particular—the Christian—god. So I don't just feel a terrible sense of imposition but, much more, I feel a loss of that culture that then got so intertwined with not only the Christian religion but also Western colonialism.

“My parents—yes, both of them—really felt a need to deny everything about themselves. Except my grandmother held true. But then when she went back to Trinidad, she'd been away for about thirty years, and when she went back her farm was gone and the whole city of Port of Spain had been very urbanized. She was quite old by then. And when she went back for her first and last visit, she never talked about any of that again because everything she’d known had been totally erased. And so part of my work is that joy of her telling those stories and living that life, that as a child growing up, even though she was surrounded by all of these spirits, a lot of them were protective. And so that's what I really want to show: that something mysterious is also something that's beneficent.”

Maile’s art has been featured at the International Print Center and the Feminist Artists Collection of the Brooklyn Museum; her honors include a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant and a Joan Mitchell Studio Grant. The variety of her output suggests the excitement of someone gleefully trying out different methods and technologies of visual self-expression: paintings, sculpture, monoprints, lithographs, linocuts, varying degrees of realism and abstraction, varying intensities of color, references to fairy tales and industrial safety posters, Dayak murals, Hokusai and Hiroshige-- everything up for grabs. Birds and animals are everywhere. And in one of my favorite of her pieces, “Picnic with Nuclear Butterfly,” there’s a monster: Godzilla with two pairs of butterfly wings roaring down at the shadows of some very scared- looking humans and what appears to be a nuclear reactor.

“Godzilla is this thing that’s one of its kind, melancholy and lonely,” she says. Godzilla is a monster, but it’s also us, homo faber, hominus factorum, man the maker, man the made, frantically excising ourselves from the web of organic existence even as we set it on fire. “We are creating ourselves as a monster that has no connection to anything.”

I think of Maile as one of the heroines of my book, heroic in her commitment to art-making and her willingness to follow the creative impulse wherever it led her. Heroic also in her modesty and sense of humor. “I grew up very poor and with very limited access to the outside. I went to Catholic schools, everything was on one journey, and that was the journey towards God and marriage and nothing else. So when I began writing plays and moved into Westbeth, it wasn't that I wanted to be a playwright: I just wanted to experience every single thing because I had never done this before. That's why playwriting to me was the same as being a carpenter. And then being a carpenter and a playwright, and being involved in theatre was how I got into landscape architecture. So it wasn't that I wanted to be a playwright, or a carpenter or landscape architect, I wanted that experience of creating things out of nothing. Other people probably have different reasons. But that was my reason-- just the lure of expression.”

I knew Barton Benes. I still have some shredded currency from his memorial service (at which his friend and patron Larry Hagman spoke). His incredible Westbeth studio has been reproduced at the North Dakota Museum of Art in Grand Forks.

My BF in the early 80’s sublet a Westbeth studio from John Ashbery, who had moved to a larger place in Chelsea. He would dutifully pay John the monthly rent but John would often forget to pay it and eviction notices would regularly appear under the door.

I lived nearby in a building on Horatio called the West Coast. It was one of the earliest conversions of old meatpacking buildings to new rentals. I was told it had been used as a meat refrigeration warehouse before the renovation; despite all the modern trappings the roaches still ruled the roost.

Sincere thanks for this beautiful story. I needed reminding why we need art in our lives and this did it for me.